Dr. Howard Fuller hails from Milwaukee, the most segregated major city in the country. He says it doesn’t bother him, though.

The decorated 78-year-old activist and educator has spent a lifetime agitating for civil rights as a social worker in Chicago, a community organizer in North Carolina and a superintendent of schools in his hometown. At an age when many would consider retirement, he’s still among the country’s loudest and most eloquent voices for educational equity.

But he says the debate around racial segregation in schools has become detached from reality. In fact, he says, it’s “irrelevant” to the lives of the students at the charter school he founded — Milwaukee Collegiate Academy, which was recently renamed after him — nearly all of whom are black or Latino. Those kids, like millions of minority children around the country, will inhabit racially isolated spaces well into the future; rather than concocting ambitious integration schemes, Fuller argues, we should be working to give their families better educational options.

Those views have generated some controversial press in recent years. So has his unqualified support for charter schools and private school vouchers, which he says offer disadvantaged kids a shot at the same educational opportunities as white students in more affluent areas. Though he’s called President Trump “despicable,” he has also said that he respects Education Secretary Betsy DeVos and that he hasn’t changed his mind on the need for greater school choice.

RELATED

74 Interview: Longtime Civil Rights Activist Howard Fuller on Trump, DeVos, and What It’s Like to Advocate for School Choice in an Age of ‘Hypocrisy’

On the 65th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, Fuller strikes a glum note on the prospects for a truly integrated America. The dream of an integrated, egalitarian society, Fuller says, was built on weak foundations: Brown itself relied on questionable social science, including debatable notions of psychological harm done to black children by being kept apart from their white peers. Its successor ruling, Brown II — which followed a year later and ambiguously ordered districts to desegregate “with all deliberate speed” — was taken by Southern authorities as an invitation to dig in their heels.

“This discussion … has been going on since black people were brought here,” Fuller told The 74. “And it will go on forever.”

This conversation was edited for length and clarity.

The 74: Do you have any personal recollections of the Brown v. Board decision from your boyhood?

Fuller: I don’t think I even heard about it. I was in the eighth grade in 1954, and in the ninth grade in 1955. The other thing was that I was in Milwaukee. I don’t recall knowing anything about the Brown decision when I was in the eighth grade or the ninth grade. It had no impact on me whatsoever.

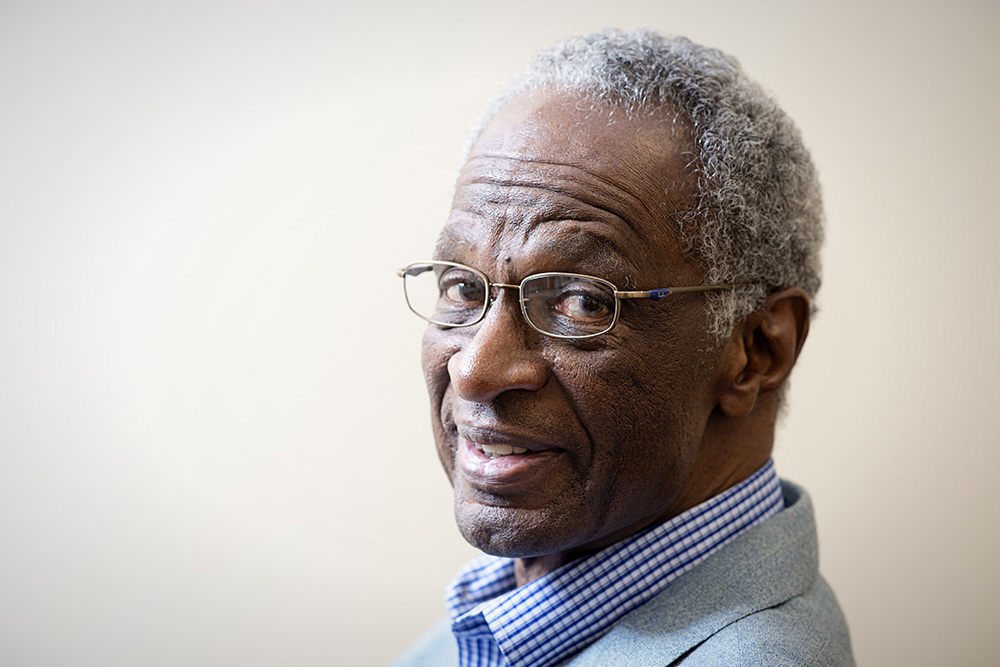

Howard Fuller (Getty Images)

You were approaching high school age in those years. You were living in Milwaukee — then, as now, a very segregated city, in a neighborhood that was quite segregated. Can you tell me what the impact was of living in an area so polarized by race?

You have to see a person like me in two ways. First of all, I was born in Shreveport, Louisiana, and came to Milwaukee when I was like 6 years old. From the time I was 10, 11, I can’t remember, I used to go back to Shreveport to visit my grandmother.

In Shreveport, I actually experienced segregation. And the reason why I’m talking about it in this way is because I have a lot of issues with the way that people characterize my position — when they say that I support segregation. That, in my view, shows a complete lack of understanding as to what constitutes segregation in America.

There were times I experienced it in a negative way, and there were times I experienced in a way that I did not perceive it to be negative. When I went back to visit my grandmother, I actually had to ride in the back of the bus. I actually had to drink from bubblers where there were “White” and “Colored” signs. If I wanted to go to see a movie downtown, I had to go around to the back and go sit up in the balcony.

For a lot of young white people, who always talk to me about what I believe and don’t believe, it presents a certain problem to me because they don’t know what they’re actually talking about. As you look at my history, you have to make the distinction between experiencing segregation — a legal apartheid — in Shreveport, and then coming back to the north side of Milwaukee, living in housing projects that were all-black.

I don’t recall feeling any kind of way about my blackness as opposed to the white kids — not in elementary school. I didn’t see it as a negative that I was living in the projects, or living on the north side, which was predominantly black. That didn’t really start until I got to high school. I went to North Division. When I was in ninth grade, it was about 75 percent white; by the time I became a senior, it had flipped to the point where it was 60 or 70 percent black.

So I actually went through the period when white people started to move away either to the suburbs or to other parts of the city, and the high school became predominantly black. I’m telling you that because when you ask me the question, “How did you feel about living in a segregated city?” — I didn’t feel any way about it. I didn’t have a political analysis of the situation in the ninth grade. I didn’t.

When we played basketball, our team was predominantly black in my junior year. We had one white dude who was a starter. We were really close friends. By the time I became a senior, our team was all-black. We were rated, like, number two in the state. We played on the first team from Milwaukee to ever go to the state tournament. So we were playing these white schools, both in the city and from the suburbs, and we clearly wanted to beat them — not just because we wanted to win, but because they were white.

For example, since we had such a great team, different schools in the suburbs wanted to scrimmage us. I recall going to a scrimmage out at Milwaukee Country Day School, now University School of Milwaukee. It was this big-time private school, right? We go out there, and these dudes — it was a boys’ school. They had cars, there’s only three or four in a class, they were in suits for sports. And I remember us in the dressing room like, “We gonna kill these dudes.” (Laughs)

Which we did. I mean, we destroyed them. But a part of the motivation was our looking at, “This is how they live, this is how we live. The one thing that we can do is, we can destroy them on their basketball court.” This was when I was a senior, so I was beginning to clearly understand the difference in that world versus the world that I lived in. It was a reflection of both race and class. It wasn’t just race. But because they were all white, that’s what we focused on.

I’ll give you another example. When I was in the 10th grade, and I played on the fresh-sophomore team, we went to play in a suburb right outside Milwaukee called Port Washington. We had this coach, Mr. Pelican — white. I only had two black teachers the whole time I was in high school. Mr. Pelican was from the South; he was a phenomenal man.

Mr. Pelican had this drawl. He was like, “Now boys, we’re getting ready to go up here to Port Washington. They got a boy on their team, and his nickname is ‘Nigger.’ His father’s nickname was ‘Nigger,’ his grandfather’s nickname was ‘Nigger,’ and his nickname is ‘Nigger.’” This is how stupid we were then. (Laughs)

What Mr. Pelican had done was skillfully prepare us to be called niggers. But we never knew which dude it was. So they were saying, “Nigger,” and we’re going, “Oh, they’re not talking about us. They’re talking about whoever this guy is that’s on Port Washington’s team.”

This is a true story.

It sounds as though in your adolescence, you were gaining a recognition that these were racially segregated schools. But it also seems like you didn’t feel this sense, and I’m going to quote from Earl Warren’s opinion in Brown, when he said, “To separate [some children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status.”

That’s one of the problems I have with Brown, even though I believe it was revolutionary. But most people have never read Brown — have never read Footnote 11, which is where all the social science literature is that says there’s a basis for that statement. That statement is the fundamental problem I have with Brown.

I’d make a distinction between segregation and racially identifiable schools, because to me, segregation is a set of rules, laws, regulations, policies that force people to be located in a certain place because of their race and wouldn’t allow them to do certain things because of their race. That I will never support. That’s why when people say, “Fuller says segregation is OK” — they’re using what I would say is a racially identifiable entity, as opposed to segregation.

To quickly return to those visits south you took when you were younger: It occurs to me that when you made those trips, you would have been almost exactly the age of Emmett Till when he visited from Chicago on a similar trip. He was visiting relatives in Mississippi, whereas you were going to Louisiana. Those trips must have been eye-opening, as different as those places were from the world in which you were raised.

Sometimes I went by myself. I rolled on the train. And so when I got to Texarkana, which is where I remember having to change trains, there was a black section. Sometimes my mother and my stepfather would drive me there, and I remember clearly packing chicken and all of this stuff. Once you got past St. Louis — which is sort of like the Mason-Dixon line — there was no stopping. There was no, “We’re going to go to a restaurant.”

My stepfather and my mother prepared us for the trip. They had to map out the route and what we could do when and where. So, I actually experienced that — which is, to be honest with you, where some of the anger comes from when some young white person starts lecturing me on the ills of segregation. I’m like, “Hey, man, who do you think you’re talking to?”

Let’s open this up a little bit. A belief that’s widely shared — and seemingly backed up by social science — is that American schools are more racially segregated now than they were 25 years ago. After gains in the ’70s and ’80s, there’s been a considerable amount of backsliding, some would say.

Do you believe that American schools are becoming more segregated — that black, Hispanic and perhaps Asian students are more racially isolated than they were previously? And if so, does that concern you?

One of the problems that I have with even discussing this is that there are so many terms that have been accepted on their face. Let me start with the fact that I don’t even agree with how so many people even characterize the problem.

One of the great hopes that exists is that somehow, we’re going to have an integrated America, and schools are going to be the vehicle for it. We don’t have to do anything about housing policy. We don’t have to do anything about employment policies. But somehow, we’re going to integrate America through schools. That is a gigantic hoax.

What we have to do, I think, to have a serious discussion about this is go back and put Brown within a larger context. Gloria Ladson-Billings talked about this in an article that she wrote. What’s really interesting is, Brownwas not really the catalyst for the civil rights struggles in the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, right? It really wasn’t Brown. Brown was one important blow against legal apartheid. But if you really think about it, people were much more focused on riding in the back of the bus. Employment. Voting rights. Later on, housing.

So, let’s stop here for a moment and quit pretending that the “desegregation of schools” is the most important thing that could be done for those people to live in an integrated America.

For me, a lot of this discussion about integration or desegregation or segregation, whatever words people want to use, it’s theoretical and abstract. Because the reality on the ground is that, for poor black children and many poor brown children, if we don’t figure out how to get good schools for them in the areas in which they live, they are not going to have them. And I do not foresee how, in the near future, for the vast majority of them, integration is a real option. I think it’s the kind of thing that people talk about on college campuses, that liberals talk about when they get together, or conservatives, who always talk about it. But on the ground, we’ve got to figure out how to get to good schools for most of them in the communities in which they live.

Chris Stewart of Education Post is somebody who’s aired similar views over the years. It sounds as though the reality of racially segregated schools is so great that perhaps it’s best to simply make sure that there are good schools for black or Hispanic students regardless of whether they’re integrated, and that that’s what the focus should be on. Is that an apt characterization of your view?

No. Here’s the best characterization of my view.

First of all, if you don’t say nothing else in this article: I oppose any situation where black people or brown people are denied access to anything legally, or quasi-legally, because of their race. Let me be very clear about that. The reason why I’m saying that is because even in the way that you characterized it — “racially segregated schools are OK” — what I’m saying is, racially identifiable schools are a reality for the kids that I’m dealing with every single day. But I will never be opposed to anybody who says, “I want to create an integrated school,” whether you want to create it based on race or economics, like High Tech High. I would never oppose anybody who has an idea like that.

What I’m saying is, I could never envision an America where this issue is resolvable. It’s not resolvable because we just are not willing to accept that racism and white supremacy is built into the fabric of American society. And anybody who thinks that there’s going to be a way for us to get beyond that, to me, is living in a dream world.

All you’ve got to do is look at W.E.B. Du Bois. Look at “Pechstein and Pecksniff” [an essay in which Du Bois argued against segregated education], that’s in 1929. Then in 1936, you read the Journal of Negro Education, and he’s making a case for why you need all-black schools. What I’m saying is, you all keep talking about this like one of these views is going to win. That’s never going to happen.

The reality of it is, this discussion, debate, whatever you and I are having, has been going on since black people were brought here. And it will go on forever. So I’m not mad at the integrationists. I have no problem with their view. I do have a problem, though, when they try to tell me that this is the only solution, and that this is what we all ought to be working on. That, to me, is absurd.

It does seem obvious that this is a complex problem that, if ever solved, will take decades of changing residential segregation and zoning patterns, and even a more elemental evolution of white people’s attitudes about where they’re going to send their kids to school, and who they’re going to accept in their kids’ schools.

And yet at the same time, it seems like we should at least try to prevent the problem from getting worse — and, insofar as there are policies that are deepening segregation right now, states and cities should be correcting them.

I don’t disagree with that. My issue is when you try to tell me that [integration] is what we’ve all got to be doing. See, the difference between me and some of the integrationists is that they want to try to characterize me in a certain way — “Oh, he supports segregation. He’s this, he’s that.”

I don’t spend my time trying to characterize them in any kind of way. All I say is, for people who want to do that, God bless them. And I hope that they’re successful. If that strategy helps a lot of our kids, I’m for it. In the meantime, I’ve got a certain reality that I see every day. And if I was to stop dealing with the reality that I see every day and go engage in this debate, these children right here, right now, would have no hope. No hope.

When you mention “the integrationists,” are we talking about the Century Foundation? Maybe Nikole Hannah-Jones?

There’s a YouTube video out there. I debated [Georgetown professor] Sheryll Cashin at the Century Foundation on this very question. And so people like Chris [Stewart], they deal with Nikole Hannah-Jones. I don’t deal with these people, man. I don’t mean that in a disrespectful way, I just don’t run in those circles. What I’m generally focused on is the day-to-day reality of the kids that I’m trying to help. I’m sitting in this school right now, talking to kids about things like, “Your temper: What’s going on inside of you that caused you to explode like that?” I’m dealing with kids who are essentially homeless. I’m dealing with a kid where his mother puts him out. He slept on the roof of the library, you know what I mean?

Certain discussions are just not — they’re not real to me. They’re functioning at a 30,000-foot level, right? And I’m not mad at people. What I’m saying to them is, I hear what y’all are saying, that’s very interesting. I’m sure it can work at the level of theory, and maybe, in certain communities, you might be able to pull it off. Great. But in the community that I live in, and for the kids that I’m trying to represent in our school, that discussion is irrelevant.

But just look at all of that social science literature [quoted in the Brownruling] — and that’s just some of it — it leads you to a conclusion that something that is all-black is, by definition, inferior. And so two things we learn from Brown, or at least I learned: Number one, we really didn’t understand the degree to which white people were going to resist this — the level of vitriol, and what they would do to make this not happen. Because people like to talk about Brown I, and then they don’t realize that Brown II was really a capitulation to those interests.

The nature of the comment that something that is all-black is by definition inferior — I’ve always had a issue with that formulation. And I think the formulation, in part, comes from the type of social science literature that was in vogue at that moment in history.

The second thing that we never dealt with was the impact of the Browndecision on black institutions. And so like Michele Foster describes in her book, Black Teachers on Teaching: Three things happened with integration. Black schools were closed. Black teachers lost their jobs. Black teachers’ opinions were devalued. With ed reform, three things have happened: Black schools have been closed. Black teachers have lost their jobs. And black teachers’ opinions have been devalued. And I say that to say that, no matter what the policy is, somehow the black community as a community is impacted negatively.

In Milwaukee, I did my dissertation on the discriminatory implementation of desegregation. You know why? Because white people said, “There’s no way we’re going to come into the black community unless you get rid of the black children, create new schools, do all the things that we need. Unless you build into the law that no school can be considered integrated if it’s predominantly black.”

Milwaukee is the most segregated metropolitan area in the country. You grew up there, you were the superintendent of schools there. Can you tell me any lessons you’ve gleaned either as a long-term resident of the Milwaukee area or as a superintendent? What it is like to lead efforts to improve schools in a place that is largely racially divided?

I just finished reading the book Selma of the North. It’s about Milwaukee, but what it focuses on is the Open Housing Marches in 1967. What Selma of the North is about is what you’re talking about: this whole notion of the segregated city, trying to get open housing. And then I read Evicted, which is talking about Milwaukee again, but it’s talking about the problem of poor people getting housing.

Even though you have all of these laws that are on the books, poor black people, poor brown people — poor anybody people — can’t get decent housing. So when you say, “Whoa, you live in the most segregated city, Milwaukee” — Kevin, that don’t bother me, man. What bothers me is that there are 27,000 households in the city of Milwaukee with a household income of less than $10,000. It bothers me that 65 percent of the households in the city of Milwaukee have a household income of less than $50,000. What bothers me is to see gentrification taking place in the area of the city that used to be all black, and now poor black people are being pushed to the edge of the city.

So it didn’t bother me, when I was the superintendent, that I was the superintendent of the so-called most segregated city in the world. What bothered me was that I didn’t have enough great schools for my kids. What bothered me was that when I tried to go out to get a referendum to build new schools, it was defeated by the taxpayers. So it’s a problem with the way the entire conversation is framed; and therefore, all of these assertions and assumptions that come from the way that it’s framed.

I live on 44th and Concordia, and I’ve lived there by choice. I live in a community that, at one point in time, was integrated. Now, the only significant number of white people that live in my community is an Orthodox Jewish enclave two or three blocks from me. And that really don’t bother me. What bothers me is the lack of power, the lack of resources, that exists for my community. And to be honest with you, I cannot envision a so-called integration strategy that is going to change that, because if you think that our city is now being integrated? It’s being gentrified.

I don’t know how else to say it. I didn’t think one single day — one single moment — when I was superintendent that the issue of “living in a segregated community” would come across my mind as something I needed to focus on. I needed to focus on, “How do I try to create really good schools for my kids? How do I deal with the type of violence that they experience every day? How do I deal with police killings?” Those are the issues that impacted my mind. What impacted my mind was 17 kids died while I was superintendent. They were killed, a couple kids committed suicide, some kids died because they were in a house that burned down.

That’s what impacted me. Not this idea of segregation — because I know with the Democratic convention coming, that’s all you’re going to hear. All of these Democratic candidates are going to come up with all of their proposals and blah, blah, blah. And some of them are going to be significant. Some of them would amount to major social change in America if they were to occur. Although I think some of them will never happen in my lifetime — maybe somebody else’s lifetime. But the issue that we’re debating, and the manner in which we debate it, is part of the problem.

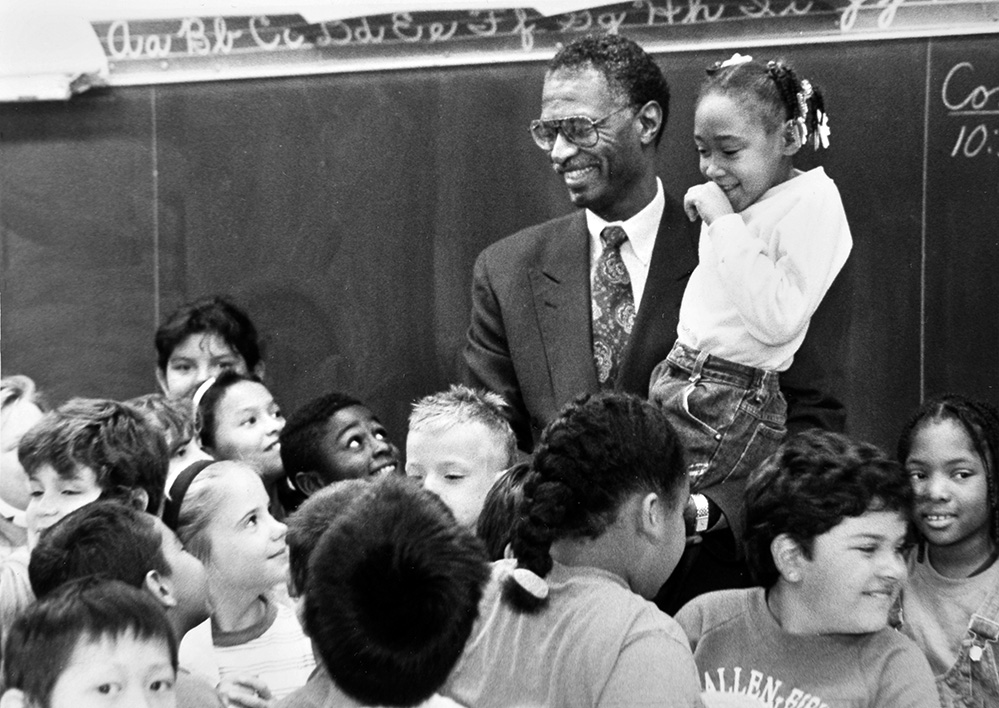

Howard Fuller with a group of Milwaukee Public Schools students in the early 1990s. (Howard Fuller)

I’d like to follow up on your remarks on how American society has progressed with respect to racial integration. Demographers will say that we’re living in a substantially less segregated society than 25 years ago or 50 years ago. Partially this is because you’ve got middle-class whites coming back to urban cores and a lot of black people moving to the suburbs. And yet, as you noted, a lot of that movement is just driving higher rents and attracting amenities that are not enjoyed by anyone other than the white people who are moving in and gentrifying. And so this move toward greater residential diversity might not really be any progress at all.

The question is, what did we learn in these 65 years since Brown? Donald Trump was not elected by five unemployed white people in West Virginia. If you read [Ta-Nehisi] Coates’s book, We Were Eight Years in Power, in the article, “Donald Trump Is the First White President,” he details the fact that Trump won every white sector of American society.

Does this have anything to do with the fact that they’re projecting that in 2044, for the first time, white people will be in the minority in America? Does that have anything to do with policies that say, “We’re going to build a wall, we’re going to put all of these people out. Then we’re going to go to Norway and get some white people?” While we’re having this discussion about integration, there’s another whole half of American society that’s having a totally different discussion.

Does it ever give you whiplash to go from that kind of ambitious talk of integration and social change, and then to look at the political reality of the Trump presidency?

Yeah, it does. A lot of people who criticize me for being whatever it is I’m supposed to be — they don’t really understand that my commitment to social justice is probably closer to theirs than they would think. But they’re fixated on integration as the litmus test for whether or not you are “progressive.” All of which I find ridiculous. It’s an issue of the moment in history in which you live, and just because you did something that was progressive in 1930, do you get to hold on to that? Is it not tied to the particular set of circumstances that you are facing at a certain moment in time? Those are the kinds of lenses through which I look at these debates.

You use the word “whiplash”: It is kind of difficult, because there are things that people will say who are integrationists that I believe in too. There’s some things that so-called conservatives believe, and I believe them too. Because I think if you’re black in America, you cannot afford to be in any of these camps permanently. Because the government has oppressed black people, the private sector has oppressed black people, you know what I mean? There’s none of these that is necessarily better for me than the other.

No permanent alliances, only permanent interests?

Yes, in politics. I do have have permanent friends from a personal standpoint. But in the political realm, what you just said is real. But even having said that, you do have to draw lines.

Like, for example, I could talk to George W. Bush, who I got to know. I had conversations with him, and I took a lot of flak for even talking to him. But George Bush — I didn’t believe everything he said, but he’s fundamentally a decent human being. For some people, meeting with George Bush was a matter of principle. For me, it’s a matter of strategy or tactics. But when it comes to Trump, it’s a matter of principle. Everybody draws a line.

Is there something that one of the 22 Democratic candidates could say — on education perhaps, on school choice, on education spending, school autonomy — that would pique your interest? Is there something that you’ve hoped to hear?

No. First off, because I don’t believe much of what these people say while they’re running. So you can put me down as a cynic in that regard. And then the second part of this is that I’m not a Democrat. Nor am I a Republican. I don’t belong to either party because I don’t believe in either party. But I do believe there’s a certain reality that Trump represents that as important as education is for me, there’s some other things that are more important.

Even though education has been one of the consuming issues of your life?

Yes. Here’s where a person like me gets into problems. It’s because I have a deeper responsibility to the history of black people in this country, which is being threatened by the very nature of the positions that people like Trump are taking. You know, taking away voting rights, for example, suppressing the vote. When you start talking about things like that, that’s fundamental to a person like me.

So whatever your position is on education, when you begin to talk about taking away people’s health care, taking away people’s right to vote, all of these things —I’m sorry, but as much as I’m for parent choice and using our charter schools, those issues are fundamental to my existence as a black human being in this country.

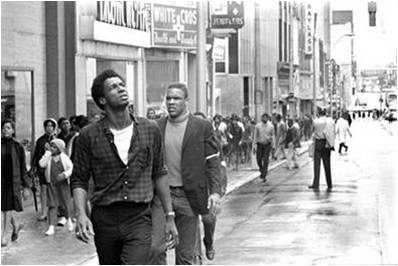

Howard Fuller, then in his 20s, leads a political rally in Durham, North Carolina, in the late 1960s. (Howard Fuller)

You spent a good deal of time as a civil rights organizer in North Carolina. That state is now holding a special congressional election to make up for one that was marked by fraud and the suppression of black votes in 2018. Is this something that you are distressed to have to confront again in 2019?

Yeah! Of course. If you read Eight Years in Power, there’s a part of it where you think it’s about Obama, but it’s also about Reconstruction, and a black state senator asking a white elected official, “Why does it make you all so mad? We did roads, we did schools, we did all this stuff.” The reality is that white people were not afraid of black people creating bad government. They were afraid that they would create a good government.

One of the things that happened during the post-Reconstruction period was an effort to dismantle everything that had been done to give black people a larger measure of freedom and citizenship in this country. I believe that some of what is being done today is the same thing. And since I’m a conscious black person who understands this, how can I not speak about it? How can I not take a position in opposition to this? This is one of those moments in history, Kevin, where silence is betrayal.

This interview was originally published on The 74 Million’s website.